LEGO

Category: Business Sub-category: Company

On Sunday mornings, my son Ari and I have a tradition. We curl up on the couch with bagels (and my coffee) and watch some of the best LEGO channels on YouTube. These are not just videos of people building sets, but of creators who bring enormous joy and imagination to their builds—assembling whole cities, creating innovative designs, or testing wild new ideas. We pause, rewind, and often debate how we’d do it differently. Ari has picked up techniques I didn’t know existed at his age, and I’ve learned too.

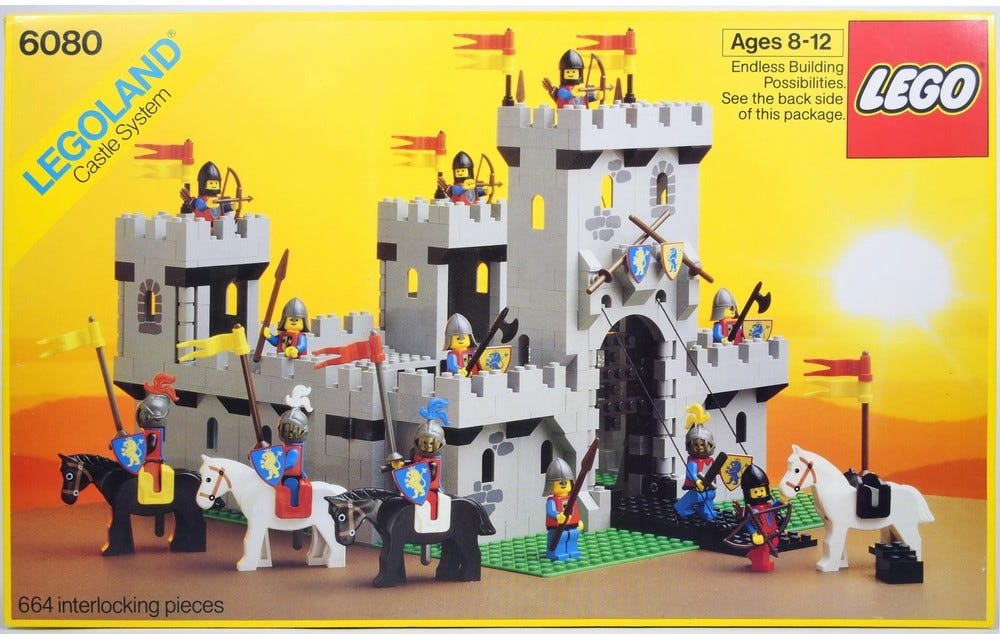

Even without YouTube as a guide, I loved LEGO more than any other toy. My first “big” set was the King’s Castle System, which I built, deconstructed, and rebuilt dozens of times. Once, I even tried to make Wrigley Field in our backyard sandbox—complete with dugouts, the famous bleachers, and a broadcasting booth for Cubs legend Harry Caray. The scale was off, but that wasn’t the point. It was about experimenting, finding out what was possible with the pieces I had.

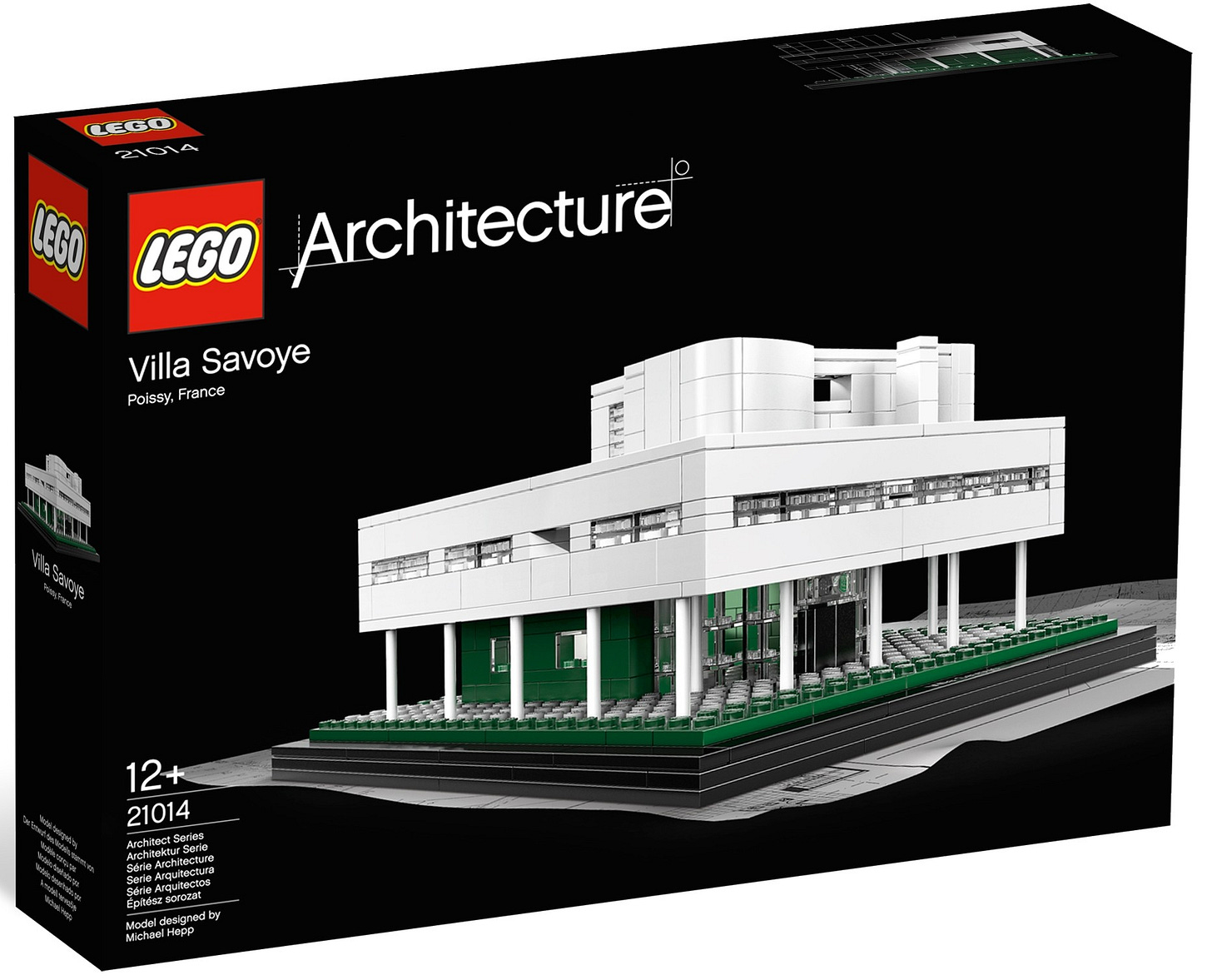

That impulse, and my love for LEGO, never left me. Today, my favorite sets are the Mondrian I made and framed (Post #15) and the LEGO Architecture models of the Villa Savoye (Post #30) and the Farnsworth House (guaranteed future post). A few years ago, at a team offsite, we built a massive Ferrari set together—red, sleek, beautiful. When we finished, we gave it to the hotel manager for her son, who was also a LEGO fan. Giving it away was at least as fun as building it. When in doubt, LEGO sets are always a great gift.

The name itself is perfect. LEGO is short for leg godt, Danish for “play well.” With LEGO, you do. Since 1958, every brick has been engineered to fit with every other brick ever made. That’s no accident—it’s design integrity of the highest order. A brick made over 60 years ago clicks perfectly with one made today, turning LEGO into a kind of universal language. Grandparents, parents, and kids, generations apart, can sit down with a pile of bricks and instantly collaborate.

The scale of LEGO is astonishing. More than 600 billion pieces have been produced—roughly 65 LEGO bricks for every single human alive since their interlocking bricks were first made. All those bricks, together, weigh about the same as 15 aircraft carriers! This all adds up to LEGO now being the largest toy company in the world by revenue, profit, and valuation—far surpassing both Mattel and Hasbro combined. But its rise wasn’t smooth.

In the early 2000s, LEGO nearly collapsed under the weight of overexpansion—theme parks, watches, video games, even clothes. Costs ballooned as the company introduced thousands of new molds for niche parts, drifting from the versatility of the core brick system. By 2003, LEGO was losing $300 million annually and was just months from running out of cash.

The family owners acted decisively, bringing in Jørgen Vig Knudstorp as CEO. He streamlined operations, slashed unprofitable lines, and refocused on core bricks and smart licensing (Star Wars, Harry Potter). This is all classic restructuring, executed superbly. However, he also did something radical: listened to fans. LEGO embraced Adult Fans of LEGO (AFOLs), crowd-sourced ideas, and created sets for both kids and collectors. The result was one of the most celebrated corporate turnarounds of the past 25 years.

LEGO’s family-owned structure (controlled by the Kirk Kristiansen family, descendants of the founder) was a key competitive advantage. Unlike Mattel and Hasbro, publicly traded and pressured to deliver quarterly hits, LEGO had the freedom to think in decades, not months. It could protect brand integrity, make long-term bets on sustainability, and invest patiently in experiments like LEGO Ideas, robotics, and digital play. That freedom has made LEGO more trusted, more resilient, and ultimately far more valuable.

And that, I think, is the deeper lesson. Creativity thrives when structure and freedom meet. LEGO shows us that well: start with a of bricks, follow instructions or invent from scratch, build then break then rebuild, discover that finite pieces can make infinite combinations. And, critically, interconnection makes bricks stronger—just like people. Each piece is small, but together they can make something remarkable. That’s the magic of LEGO, and, I hope, of Hopefully Beneficial too: small, deliberate pieces, placed again and again, until a fuller picture comes into view.

And friends, that’s a wrap on Hopefully Beneficial post #36. Only 2,464 to go. See you tomorrow. Shalom—and let’s keep going!

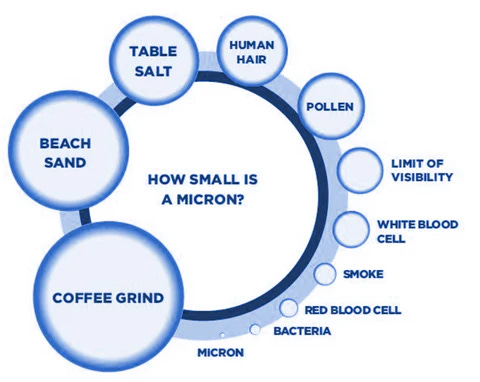

Bonus Fun Fact: The “clutch power” of LEGO bricks—the perfect balance between holding and releasing—is engineered to a tolerance of just 5 microns, one-fifth the thickness of a human hair.

Bonus Photo #1: LEGO King’s Castle, Set #6080, 1984. My favorite as a kid.

Bonus Photo #2: LEGO Architecture Villa Savoye, Set #21014, 2014. My favorite as an adult.

Bonus Video: LEGO BUILDS that seem IMPOSSIBLE... (This is from TD BRICKS, a YouTube channel that Ari and I like.)

It is great to read about the turnaround at LEGO,, thanks for sharing Ben. I loved playing with them when I was little and again when my kids were little. And LEGO is big on sustainability, hitting 100% renewable energy production equal to all of their power used (https://arena.gov.au/blog/lego-goes-100-renewable-and-sets-new-world-record/#:~:text=%E2%80%9CThis%20development%20means%20we%20have,of%20tomorrow%2C%E2%80%9D%20he%20said.) and they have found ways to increase the circularity of the feedstocks for their bricks etc. https://www.lego.com/en-us/aboutus/news/2024/march/making-lego-bricks-more-sustainable-?locale=en-us

I think this is such a fun post - lots of fun facts I never knew before!!