Fridays at Hopefully Beneficial are always about The arts. I look forward to exploring myriad facets of visual arts, literature, and performing arts here, together with you. We’ll be looking at artistic creations and their creators, and trying to figure out what it all means for each of us. This is going to be fun!

Why do I care so much about The arts? Well, for starters, I come from a family that loves them, and who especially love painting and architecture. Treasured paintings by my grandmother grace the walls of our apartment alongside masterful drawings by my father, who studied architecture under the disciples of Mies van der Rohe at the Illinois Institute of Technology. When I was in elementary school, my mother was lovingly known by all as “The Art Lady” because, once a month, she would check out prints of famous paintings from the Aurora Public Library and bring them to school. She taught us about Claude Monet, Andrew Wyeth, Mary Cassatt, and the many other artists she cherished. The Art Institute of Chicago was always a favorite destination, and one of my younger sisters was a student there before winning a scholarship to study design at Parsons (her subsequent career at Google supports the theory that excellence is a fungible asset).

As a boy, I read and re-read every art book in our house, including virtually every art-related entry in our World Book Encyclopedias, but my relationship with The arts really took off in college. On many a Friday, I would tuck into the towering library at the University of Massachusetts Amherst for the entire day, immersed in art history. On weekends, I’d walk to the Mead Art Museum at Amherst College or, even better, take the bus to Northampton to visit the Smith College Museum of Art. But it was at the Mount Holyoke College Art Museum that I saw my first work by Yaacov Agam, my favorite Israeli artist, and the subject of today’s piece.

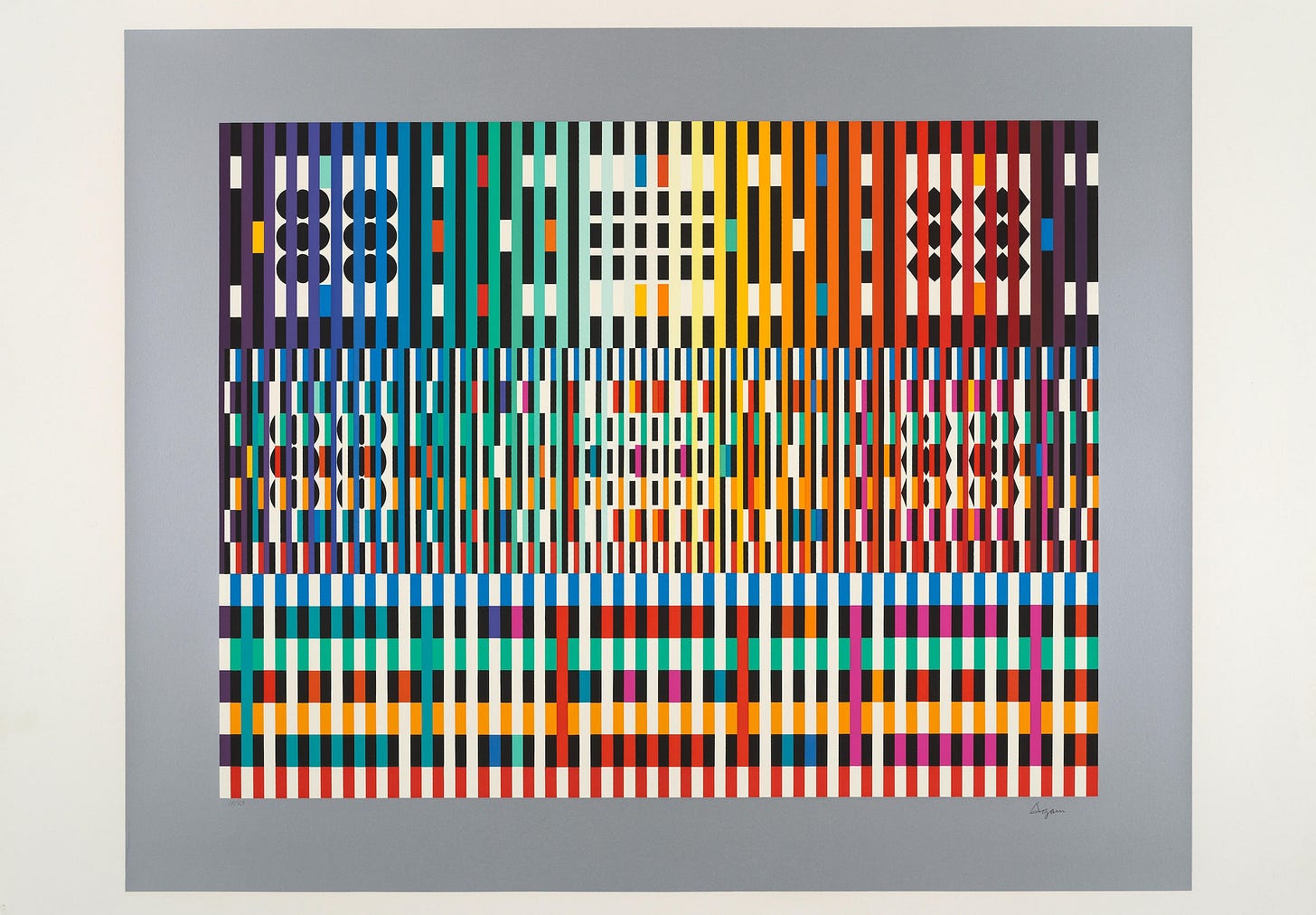

This photo is of an Agam work called Thanksgiving, and a beautiful 1980 screenprint of it hangs in our living room. Agam’s signature kinetic and optical style is dynamic and designed to be “art in motion.” His work is immediately recognizable - when guests who know Israel visit and see Thanksgiving, they comment that it looks like the famous Fire and Rain Fountain in Tel Aviv’s Dizengoff Square. You bet it does - same artist! His innovative and inventive creations often employ a “lenticular technique,” which is a fancy way of saying that they create the illusion of movement and depth, even in two-dimensional works.

Today, at the age of 97, he has been creating art for a very long time! His retrospective exhibition at the Musée National d'Art Moderne in Paris took place 53 years ago, and a similar showcase at The Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum (or, as we lovingly call it, “The Guggi”) won critical acclaim in 1980. And, fun fact: in 1977, he created what Guinness World Records have certified as the World’s Largest Menorah. Every Hannukah, it is lit at Grand Army Plaza in the southeast corner of Central Park, just down the street from where we live. His works are also in the permanent collections of the Museum of Modern Art and the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Agam was born in 1928, just south of Tel Aviv, into a deeply spiritual family. His father was a notable rabbi and a scholar of Kabbalah, the mystical Jewish tradition and school of thought. This spiritual upbringing stayed with him and has consistently informed his work. After studying at the prestigious Bezalel Academy of Arts and Design in Jerusalem he moved to Zurich to train under Bauhaus master Johannes Itten. He then settled in Paris, where he pioneered kinetic and optical art (“Op art”).

Op art utilizes geometric shapes, lines, and color juxtapositions (parenthetical: juxtaposition = my favorite art word of all time!) to create optical illusions for the viewer, and I love it. This style, along with other types of abstract and modern art, was a long-running topic of debate between my grandmother and me. She most loved the impressionists and thought that Monet, Renoir, and Degas were the pinnacle of artistic expression. I loved modern art and made the best case I could for Mondrian, Kandinsky, and Klee. In retrospect, I believe that we were both right; art’s value equals perception. We all filter the world through our own lenses, and our focus shifts across time and place. This belief is also fundamental to Agam’s philosophy. He said,

“My aim is to show that there is no reality in static things. Reality is change, movement.”

This is a worldview drawn in part from Kabbalah, and in part from his own desire to make art a living, dynamic encounter between the piece and the viewer. His art isn’t static. It isn’t passive. It asks us to participate. This approach is attractive to me, and probably one of the reasons I’m drawn to him. But also, Agam’s art simply looks and feels great. It is fundamentally hopeful and deeply Israeli, because, like Israel itself, Agam’s art does not sit still. It moves. It adapts. It challenges. It vibrates with life and tension and contradiction and beauty.

Would you like to see more of Agam’s work? I suggest starting with a Google image search for Agamograph. Enjoy!

And friends, that’s a wrap on post #10, only 2,490 to go. See you next week with more from Hopefully Beneficial. Shabbat shalom and let’s keep going!

My new favourite post!

HAPPT BIRTHDAY!!! 🎂❤️